This book contains mentions of sexual assault, abuse, and suicidal ideation.

She's not a person as much as she’s a wish. Paula, in Grasshopper Manufacture's 2011 action-adventure game Shadows of the Damned, barely exists. It's like that from the moment you find her with a noose around her neck, shortly after you start the game and become Garcia "Fucking" Hotspur.

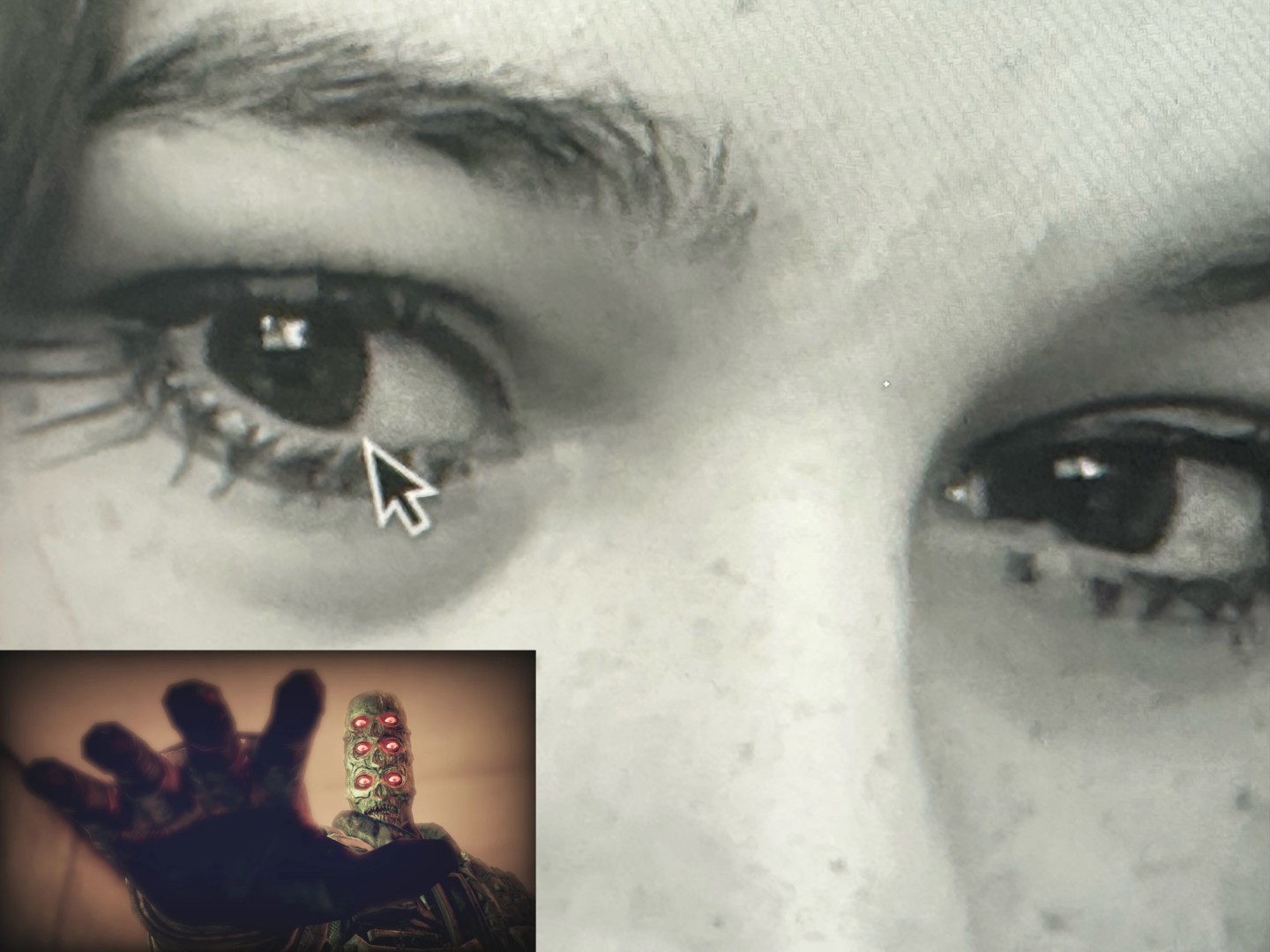

You're a demon hunter made mountainous by scar tissue and beefy biceps. You're great at your job, tattoos curl around your neck and elbows, and everything is sexy until you realize that demons are targeting your girlfriend Paula. This happens quickly — while Paula swings from the ceiling fan, her G-string peeking out, a white-eyed monster tears through her back and slumps onto the ground. You shoot at it and the horde that appears after, but your effort isn't enough to stop the demon king Fleming from taking Paula to his City of the Damned.

Women go to Hell — it's a thing we do. I've recently lost the ability to sleep, so I've been going to Hell every night, feeling foggy and faded under my comforter until the sun turns morning red again. Red is the color of Hell, and of leaking pomegranates, the fruit Hades gave to Persephone after forcing her into his underground bedroom; "Down the deep abyss the chariot plunged," Roman poet Ovid recounts in his Metamorphoses.

Not me, but some storytellers will try to convince you that women like it like that, in Hell. Take the fifteenth-century clergyman Heinrich Kramer and his instructive Malleus Maleficarum, for example, which instructed pious men to excise girls who don't behave. Disobedient witches "have made a treaty with death and a compact with hell," Kramer says, and so terrorizing them is contractual.

In the game, Paula exists for this kind of demolition. It's part of her mythology. Shadows of the Damned suggests she is a fabled demon huntress — "the first woman of her profession," says Garcia's shapeshifting demon companion Johnson. Once upon a time, the huntress dared to take on the undefeatable demon lord Fleming. To punish the woman for her confidence, Fleming ripped away the huntress' arms, then he lopped off her legs, and then he threatened to rape her.

"I could take you right here and now," he said.

"You might take me," she replied, "but you will never have me."

Impressed with her resolve, Fleming reassembled the huntress' mutilated body. He decided to keep her close so he could kill her over and over again, "just to take pleasure in her proud refusal to be dead," Johnson says. The legend goes that the huntress clawed her way out of the Underworld knowing that she deserved to walk the earth with dignity. But after Paula is abducted at the beginning of Shadows of the Damned, she's forced back into this sick cycle of pain she risked her soul to escape.

I was ten years old, praying for a state between life and death. Suicide wasn't an option, because I was too afraid of Hell. And I didn't know the words "Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder,” a diagnosis that would eventually define my life. But I could sense that something in my brain had gone dark.

I suspected demonic possession.

I was clinically obsessed with the idea that Satan — with deformed horns, and a cinnabar-colored six-pack — was after me. Compulsively, I avoided the number six and eating food. Cherries, jello, and chili peppers were too red, too hellish; if a strand of my own black hair landed on my sandwich, it was ruined. Sure, it looked like my hair. But what if it was, instead, a coarse strand of a demon's bushy tail? What if eating the sandwich, having been contaminated with demonic energy, infected me with ghosts? What if these ghosts ripped my soul from my body? What if my sallow flesh was the perfect vessel? What if Satan entered through my mouth while I was sleeping? What if I was destined to burn? What if I screamed and nobody could hear me?

What if my nightmares were real?

"Help me, Garcia!" Paula pleads as blood seeps through her pores, spilling down her white dress.

After Fleming takes Paula deep below the Earth, Garcia dives in after her skull-first, kicking off the grueling quest to get her back that makes up Shadows of the Damned. While fending off monsters in your slow crawl toward Fleming's castle, where suffering Paula is detained and beautiful, you occasionally run into what seem to be projections of her. In this instance, Garcia stands in front of Paula's crumpled frame, staring with his studded jacket on, as the blood becomes more aggressive. It bubbles from her stomach like a water fountain, and Paula clutches herself like her hands are the only thing capable of keeping her together.

"Why, Garcia, why!" she begs. "Why am I bleeding?" Garcia's breathing becomes more anguished, but Johnson commands him to stay back. Then Paula is gone.

Throughout Shadows of the Damned, Paula is a slaughtered pig to be dissected, devalued, and tasted, and her disenfranchisement is the source of Shadows of the Damned's horror. And, even with how juvenile Shadows can be as a butt-blasting shooter, it is certainly a horror game.

It was produced by Grasshopper’s Goichi Suda, who is far from a horror newcomer. Before Shadows, in the ‘90s, he directed two installments of the Japan-exclusive horror adventure game series Twilight Syndrome, as well as the Grasshopper's 2004 survival horror Michigan: Report from Hell. Resident Evil creator Shinji Mikami co-produced Shadows, though the game amusingly lacks any of the latter's restraint. Mikami told The Guardian in a 2014 interview that he prefers to avoid "ridiculous breast physics" in his games and other kinds of "obvious eroticism."

"I also don’t like female characters who are submissive to male characters, or to the situation they’re in," he said. "I won’t portray women in that way."

Shadows of the Damned doesn't share these reservations. Crassness is what Grasshopper Manufacture is made of. Like in 1999's The Silver Case, where protagonist Akira is nicknamed "Big Dick," or 2005's Killer7, where wheelchair-bound Harman Deltahead is raped while he's sleeping. In 2010, a year before Shadows released, Grasshopper expanded its portfolio of juvenile humor with No More Heroes 2: Desperate Struggle, a hack-and-slash sequel in which protagonist Travis leers at the assassin Sylvia until she finally fucks him. Suda, who wrote Shadows of the Damned, at least glosses Shadows' lewdness with an impressive soft rock soundtrack by Silent Hill composer Akira Yamaoka.

But sweet guitar couldn't save Shadows of the Damned from commercial struggle. A month after its release, the game had sold only 24,000 copies in the U.S. Despite this, the game's existence as an X-rated Divine Comedy has certain irresistible qualities (even if it began life not as a Dante Alighieri adaptation, but rather an adaptation of Franz Kafka’s unfinished novel The Castle). Its script and environment are both filthy and bold, so Shadows has always enjoyed the cult status that many Grasshopper titles are haloed with. As a result, in a PlayStation blog promoting the game's release, former EA producer Steve Matulac boasted that Shadows "is the thinking man’s shooter." Or put another way, "Resident Evil 4 rewritten by a 12-year-old obsessed with dick jokes," as Game Informer wrote in a review.

As thinking men battling devils (in their minds, on their shoulders, in the alleyway next to the dive bar…), Garcia and his weapon — Johnson — congratulate each other for their resilience and determination. They have reason to. Even the game's standard-issue bald demons, which lunge at you with their sharp nails or vomit out bloody projectiles, are obnoxiously persistent and unpleasantly deadly. You have to dispatch them using Johnson — OK, Johnson, as in penis, yeah.

When Johnson's floating head turns into a standard handgun, it's called the Boner. You can eventually upgrade the Boner to the Hotboner, whose item description instructs you to "hold the secondary fire button to charge, then release it to deploy your sticky payload. Shoot the payload for a thrilling explosion." The end of Shadows of the Damned ultimately offers you the rare opportunity to turn your Hotboner into a "Big Boner" by letting Johnson call into a phone sex line.

"Oh my god ohmygaga oh ga ohmgaaa SCHA-WING!" Johnson shrieks before sprouting into a gatling gun Garcia holds in front of his crotch, managing to both obsess over anatomy and make a Wayne's World reference in one go.

"Taste my Big Boner! It's good! Take that!" Garcia shouts while wielding his Big Boner during a city defense sequence. During it, you stand mostly still, aside from sometimes swiveling your Boner around, and shoot demon goliaths in the head while they approach you as slowly and safely as a distant yacht to a harbor.

Indeed, in the most perfect representation of a dick-measuring contest, most of the game's boss battles are inflected with sexual jealousy. Before each fight, you and Johnson leaf through yellowed storybooks detailing how the "VIP" demons you're about to face off against ended up in the City of the Damned. Many of these backstories involve erotic elements unrelated to the combat you're about to engage in. Rather, they help establish a smugness toward women which occasionally harms the game's overarching premise: you're a guy who loves his girlfriend so much he'd go to Hell and back.

The first fairytale you encounter, The Man Who Never Had His Fill, is meant to serve as a biography for the boss George Reed, an insatiable man who expertly played his harmonica in exchange for piles of food.

"Yet for all he consumed, George only got thinner as he washed from town to town," the book says. Eventually, he meets a woman at a bar. "And that night, George proved it as he buried his face in Mary's beaver."

"But even after five trips to heaven and back, he had not had his fill," the book continues, making the intriguing implication that a harmonica player with a wasting disease would have the strength to be great at eating pussy. The storybooks regarding female bosses are similarly boorish. Psychopomp & Circumstance, which explains the scythe-wielding Sisters Grim bosses' background, specifically mentions that sister Maras' "nipples responded to the weather and thoughts of her lover" moments before she tumbles down into a well.

"'Motherfudge! Motherfudge!' cried Maras," says the book, now neglecting to inform us of how Maras' nipples responded to the sudden increase in darkness and humidity.

Justine Divangelo, a demoness opera singer with bullets strapped to her hips and blonde curls, is given a bit more credit. You interact with Justine the most of any boss in the game. She flounces through Shadows of the Damned's five acts, evading your capture through interpretive dance moves and singing what Johnson calls her "melody of death," which causes earthquakes. Once you finally catch up to her, you experience the most innovative boss fight in Shadows.

With Justine, Garcia and the rest of the City are turned into floating shadow puppet miniatures. Flying through ice cream swirls of white clouds, you hit goat head lamps with Light Shot — a secondary, illuminatory fire mode — to clear the health-zapping, thick purple Darkness you encounter throughout Shadows. Finally, you arrive at a massive version of Justine, who threatens to crush Garcia like a bug in her fist. Deploying your Hotboner, of course, neutralizes this threat.

But as formidable as Justine is in gameplay, her storybook, Beauty is Blind, dismisses her as simplistically vain.

"After curtain-down, she retired to her dressing room, set her horned Viking helmet aside, and waddled up to the mirror with a gelatinous jiggle," the book says. A suitor comes to woo Justine, but she rebuffs him on account of her being "a fat twat."

"She tried adjusting her midriff. Disgusting," the book continues. She vows to become thin after that, and she's ultimately found naked, beautiful, and bloodied in her apartment.

"Her throat had been savaged; the blood had painted an inverse bouquet of roses on her chest," says the book. "The woman held her own vocal cords in her hands."

He didn't understand me. My father, whose snarling that I was disappointing sometimes launched spit at my face, didn't want to understand me. I had been locking myself in my room and sleeping under three crosses, mounted to my wall. To my anguished mind, every night was the same. The Devil was coming. The Devil was coming and he was going to take me to Hell.

I saw clear images in my head — the unwanted intrusive thoughts that define O.C.D. — that detailed what I had started to think of as my fate. Me, barely pubescent, alive for only eleven years, chained to a wall in Tartarus. There would be goblins at my feet, and they'd lash me with rusted chains until blood pooled under my Ed Hardy shirt. Satan would watch with a smirk on his angular face and he'd hiss things like "You're mine," or, "You belong here."

Yes, I deserved hell. I was pointless and read too many books, like my dad said. He tried being gentle once or twice during my first year of acutely experiencing mental illness. I'd become pale and quiet, and he'd noticed.

I was in my room one day, praying to Mary. Before that, I'd been compulsively reciting a passage from the Bible: "Do not gloat over me, my enemy," begins Micah 7:8. "Though I have fallen, I will arise. Though I sit in darkness, the LORD will be my light."

My dad walked in. I recoiled, but I asked him what he wanted.

"Don't be depressed," he said sheepishly. "Just be positive." He turned around and left the room.

I think we can say, at this point, that Shadows of the Damned is a game for boys.

That's a regressive statement, I admit, and I can't shirk my responsibility to state the obvious: entertainment and emotion have no gender. They never have. And yet, reaching gender parity in games is a constant uphill battle.

This has been accurate for as long as video games have been a popular pastime, despite the fact that women have made up a major demographic for a notable portion of the industry's history. In 2000, for example, a study by the now defunct market research group PC Data indicated that 50.4 percent of online gamers were women. But facts never deter misogyny.

The contemporary gaming industry loves to appeal to its platonic ideal of a Straight Male Gamer with sex and excess. Like, throughout the E3 gaming expo's history, and even after it imposed a $5,000 fine on booth owners using "sexually provocative" marketing tactics in 2006, "booth babes" wearing tight shirts and bikini bottoms enticed men to the latest Tekken. This was considered an appropriate role for women in games — unessential to the pastime, and easily accessible as a fantasy. Meanwhile, in 2005, an Urban Dictionary entry indicated that a real-life "gamer girl" was indeed "A rare species of female which makes up less than .02% of the population. Under most circumstances an uggo or is really fat."

For a more recent example of misogyny's growing stain on games, you only have to look at the glowering Gamergate hydra. In both 2014 and 2024, a certain subset of unimaginative gamers have maintained that women in games should be intimidated out of the industry.

Over the years, they've accomplished this through desperate means, including paranoid hate mail and Reddit threads they've used to target an endless list of women in the gaming industry, including me.

So maybe you'd think I should be counteracting this history. Perhaps I should run through New York with "VIDEO GAMES FOR ALL!" plastered on my lower back. But I'm not trying to be a hero, I really mean it: Shadows of the Damned is for boys.

That's not an inherently bad thing. In fact, in Shadows' best moments — say, a joke that catches me delightfully off-guard, like when Garcia muses that "beauty is only skin deep, and that bitch has no skin" — it makes me want to engage in exciting pastimes like "ice hockey" and "Red Bull." Garcia and Johnson clearly feel similarly. As you inevitably take damage throughout Shadows of the Damned, the little green bar that indicates your health on the side of the screen depletes. To restore it, you must applaud yourself by finding or purchasing fat bottles of hot sake, tequila, and absinthe from vending machines.

"In the Underworld, you don't die from drinks," Johnson says. "They "UN-kill people here."

This mechanic turns Garcia into a kind of motorcycle-riding Joan of Arc — the French martyr reportedly treated herself to several slices of bread dipped in wine while recovering from an arrow wound to the neck.

But Garcia's version is tinged with more theatrical machismo, which Shadows of the Damned borrows from the road movie subgenre. Garcia often excitedly refers to this genre during the most promising parts of his quest to retrieve his hot girlfriend, like when he's running through the street with his best friend Johnson, whom he loves very much.

Road movies originate from the earliest days of Hollywood when films like It Happened One Night (1934) and Sullivan's Travels (1941) mapped time away from home to being bossy and lascivious with a beautiful woman like Veronica Lake.

But Shadows of the Damned borrows its style — bad words and hellfire — from contemporary road movies with a more nu-metal bent. I especially see smoky whispers of Death Proof (2007), Quentin Tarantino's contribution to his Grindhouse double feature with Robert Rodriguez, who contributed the horror comedy Planet Terror.

Like Death Proof, a tarry exploitation movie about a stuntman (Kurt Russell) killing women in his car, Shadows of the Damned acts with medical-grade indifference toward much of the brutality within it, especially when it involves women.

As you trounce through Shadows' smoggy City of the Damned with your hopes high and pants tight, you'll eventually notice that all the gore piled up around wet cobblestones is female. Skinny white legs hang off of meat hooks, disembodied pairs of breasts dangle over sewers of blood, and, in those sewers, demons bite around writhing corpses' vaginas.

The implication there, possibly, is that all demons are straight men who never bothered to learn about the mysteries of clitoral stimulation. Which, fine, fair enough. But there’s also the giant naked Paula mountain.

After confronting the boss Stinky Crow, a humanoid bird you beat by shooting repeatedly in the feathery crotch, you have to walk through several stretches of Darkness hidden inside phone sex billboards. In some of them, a colossal version of Paula, a sexual assault victim, waits topless and moaning in unclipped lingerie. When you approach her the first time, she lays back for you to walk between her breasts while she sucks her fingers. The second time, she pants while lying on her stomach, and you have to run over her bare ass to reach a door. It's objectification in the most literal sense.

I was watching Phantom of the Paradise with my first love. Nineteen-years-old. Winslow was getting his head squished by the record press, leaving one side of his face looking like an overripe butternut squash.

A few weeks earlier, my love had touched me when I didn't want him to. Afterward, I fell asleep in his bed while listening to him play lullabies on his acoustic guitar. That was a bad feeling I had tried to forget. I didn't want to think about it. Not while watching a movie.

You, naturally, see a lot of gruesome shit hanging out with Garcia and Johnson. Some demons, made more hardy by a shell of Darkness they wear like armor, are particularly unrelenting. Some parts of Fleming's castle, like the breezy gardens filled with roses and bare trees, are particularly distressing in their suspicious tranquility.

Offscreen, though, Paula experiences a more insidious type of violence, one that she's given no means of combating. She's a victim from the moment Fleming abducts her — by definition, a non-consensual act — at the start of the game, but Shadows of the Damned routinely implies that Paula has been getting hurt for a long time.

At one point, Garcia recalls how Paula screamed at him "Don't answer it!" when, one day, his apartment received an unexpected phone call.

"She jumped out of her chair, ran to the phone, and ripped it right off the wall," Garcia says. "Then she came and put her arms around me, and started crying. It was the craziest, weirdest, sexiest thing I have ever seen. I have been hers ever since."

In typical meathead boyfriend fashion, Garcia talks about Paula's emotions like they're a cat's pheromones. He intimates that her vulnerability — her fear, then her tears — was something he was powerless to, an ineffable ability Paula had to make him "hers."

Shadows of the Damned seemingly endorses this position. The first time Garcia gets to interact with Paula in the City of the Damned, she's running around in lingerie as white as an angel's wing. She giggles and evades Garcia's lantern like she's orchestrating a coquettish game of hide-and-go-seek. As she hisses Garcia's name, Yamaoka's sultry "Different Perspective" plays, its 808 drums pulsing like a quickened heartbeat.

Then Garcia notices Paula's decapitated head sitting nearby. When he grabs it, it screams and laughs maniacally.

"That doesn't smell like Paula," Johnson says, "unless she's stopped showering…"

The rest of Paula's body collapses from the cart, continuing to snicker as Paula sticks her head back onto her empty neck. Johnson complains that she "killed [his] stiffy," but Paula approaches Garcia anyway, caressing his face while wondering if he came to save her.

Then a demon — the boss George Reed, that hulking, hungry skeleton with a harmonica lodged in his throat — bursts out from Paula's chest while she shrieks, now having died twice in one minute. He starts gnawing on Paula's naked legs while Johnson comments that "demons are like men, Garcia. They all try to 'get inside' the prettiest girl."

But, even within the cycle of abuse and ridicule Shadows of the Damned puts Paula in, it's undeniable that she is in immeasurable pain.

"Can't you see the little peach is coming on to me?" Fleming says when he's first about to take Paula to the City of the Damned. She wails and reaches out for help. "Now, say goodbye to Paula. She has a lot of dying to do. And coming back to life, and dying some more…I like to keep my mistresses guessing."

There's that chilling cry again.

"Yes, help her," Fleming growls. "Because in the meantime, I'll be helping myself."

When they disappear, you're left with the cold silence of an old tragedy. Like Persephone, Paula is dragged into the Underworld by her rapist. Like Eurydice, Paula must rely on a man to pull her out of the ground. "And isn’t that how it always starts," writes the poet Ann Carson, "this myth that ends with the girl ‘grown bad?’"

Shadows of the Damned is a game for boys. For women, Shadows suggests that "Death is a way to be," as German philosopher Martin Heidegger says in the existentialist text Being and Time. This is especially true for Paula, for whom death returns as often as a breath.

I was fifteen and I thought loving One Direction cured me. By that point, I'd suspected I had O.C.D., though my parents refused to let me see a psychologist for an official diagnosis or get any help.

All I could do was read about the disorder online. O.C.D. is an ouroboros characterized by unwanted intrusive thoughts and unhelpful compulsions to dispel them. I realized that I'd shown symptoms of O.C.D. as long as I'd lived. Like when I was four years old, I was terrified that I'd become pregnant by God. I'd heard about the "immaculate conception," and I had no idea how birth works, so it seemed plausible to me that I was next in line to bring Jesus back from the dead through my stomach.

I thought about it all the time, nervous and confused, until the thoughts eventually faded away. I was so young, I don't remember what changed. I probably became obsessed with kinetic sand instead.

I reached a similar ebb and flow at fifteen. By that point, I'd already gone through several phases of paralyzing fear and recovery as my obsessions changed shape with more elasticity than a rubber band. In treatment, we call all these obsessive subjects "themes." At certain points throughout my teenage years, I was sure I'd shoved my best friend into traffic, even as I continued to sit beside her in class — a product of the Harm O.C.D. theme. Other times, I tore at my skin with Lysol wipes because I felt that showers, on their own, weren't sufficient — this is a form of Contamination O.C.D., the kind TV shows like Monk tend to trivialize.

But One Direction fit comfortably into the slot in my brain previously reserved for obsessively visualizing my gory death, germs crawling into my eyeballs, or different expressions of violence I worried might be my destiny. Unlike these topics, which often involved taboo, One Direction was a more socially acceptable obsession for a young girl. And I devoted myself to the boyband with the same ritual fervor as I applied myself to compulsions, pasting magazine cutouts up and down my bedroom walls instead of burning my hands with bleach.

By supplanting the smoldering fear that had come to define my life with more cutesy fare, One Direction helped me think of boys as my deliverers from evil. I'd always dreaded sleep — the dark hid demons and potential murderers — but Harry Styles made it more welcoming. I could meet him there, in a dream.

If I couldn't sleep, there were Tumblr photos to scroll through. Harry with a beanie, Harry with a big sweatshirt, Harry with pink cat ears another fifteen-year-old must have photoshopped on. My imagination, a place I had long thought unsafe, had become perfect and clean. I was delighted, and I assumed that, once I grew up, having a boyfriend would make me permanently normal.

I couldn't just not think about it. He hurt me. I loved him, and it didn't matter.

Unlike other stories of men enduring hell for love, Shadows of the Damned tends to avoid sentimentality. After Dante endures the nine circles of Hell, for example, he's guided through Heaven by his muse Beatrice, a woman he describes as having "eyes [...] brighter than the star / Of day." But Garcia, even after diving headfirst into the underworld for Paula, has trouble finding the words.

At one point, he chats with Johnson about how he and Paula got together in the first place.

"You know I found Paula in a dumpster, right?" says Garcia, as if she was a secondhand couch he brought home. She didn't speak for weeks, making Garcia feel insecure in their interactions.

"I was afraid to even touch her, you know?" Garcia says. "Like she didn't belong to me. To anyone."

She shouldn't belong to Garcia, to anyone. Paula should, theoretically, belong only to herself — herself "moving forward then and now and forever," as Walt Whitman writes in "Song of Myself."

And near the end of Shadows of the Damned, Paula finally gets the opportunity to challenge Garcia for this perspective.

But first, there's a demon king to fell.

Once inside Fleming’s castle, there are more of his demon disciples to kill. After you dispatch Shadows' standard enemies and some hellhounds, you make it through a cellar with desiccated women on meat hooks and a courtyard weighed down by Darkness. Like any good trip to the mall, you prepare to end your journey through hell with a trip up an elevator, where you find Fleming waiting under ocean-blue clouds. He's eating your girlfriend's leg.

"Be right with you, Hotspur," Fleming says impudently. "I've still…got some fries to go with these thighs. [...] The skin is so soft and tender."

Garcia, his eyes wild with grief, shoots Fleming out of desperation. But he's too hasty — the demon king opens his heavy coat to reveal Paula within, bleeding through her dress again.

"I love you, Garcia," she manages to whisper before Fleming laughs and tears her head off with one hand. He bites into it like an apple.

After all of Fleming's acts of perverted desecration, your boss fight with him burns with unreleased rage. For most of Shadows of the Damned, Garcia — priding himself on his demon-hunting abilities and well-placed facial scars — is self-aggrandizing in combat, punctuating successful enemy takedowns with the orgasmic declaration that "It's good!" But against the towering Fleming and his three sets of red eyes, you start to worry that Garcia isn't as impressive as he thinks he is.

Fleming alternates between blasting you with his laser eyes, sending out shockwaves beneath your feet, and suddenly peeling back his coat to misdirect you into shooting Paula, who looks frozen in time, as fragile as an orchid. It's a tricky fight and gets more complicated when Fleming rearranges himself into an atomic blaster of Darkness, which you need to dispel with your Light Shot, and supernova beams that fly out of his face and belly. But if there's one thing you should know by now, it's that any problem can be solved with your Big Boner. Alternating between the Hotboner revolver, Skullblaster shotgun, and Dentist submachine gun eventually turns Fleming into a vortex of bad energy and rotten meat, and then Paula is free.

You run to take her delicate hand in yours, slick from battle. You bury your face in her neck as the credits roll, signaling peace at last.

But Shadows of the Damned isn't over yet. Paula has something to say.

I felt better for a few years. I'd learned to put a lifetime of crises behind me with the help of several mother-figure therapists, who introduced me to Exposure and Response Prevention therapy. Experts call this the "gold standard" treatment for O.C.D. — it requires you to confront the possibility of your fear without engaging in compulsions, and, at the time, I felt that it had saved my life.

I could hardly believe this. Though O.C.D. made me do terrible things to myself (through most of my teen years, I strangled myself compulsively) and think terrible things about myself (that I was a devil spawn, a serial killer, a vortex of disease, etc.), I nonetheless thought O.C.D. was crucial to who I was. I couldn't remember what it felt like to be without it.

To my shock, recovery instead helped me, a hot burner to cool off. My brain was quiet for the first time. I wrote a revelation down at one point during those years: "I hadn’t become a different person after reclaiming my life from my O.C.D.; it was more like sweeping sand off of a seashell: I had been uncovered."

In fact, if you'd asked me what role O.C.D. played in my life at that time, I'd smile at you sagely and say that I didn't have it anymore. Hadn't you heard? I put in the work!

But now, after half a decade, the lights have turned off again in my brain. Without warning, my childhood insomnia returned, though it's much worse than it used to be. My O.C.D. followed. I'm obsessed with sleep — how I slept last night, if I'll sleep at all tonight, if I'll sleep at all this week, if I should kill myself because what's a life without sleep? Isn't sleep something that makes us human? If I can't sleep, something about me must be inhuman. I must have been cursed from the moment I was born.

"Why didn't you help me? Why didn't you console me? Why did you let me die each time?!" Paula screams.

A moment ago, she put her hands around Garcia's neck and choked him with so much force, he got lifted off the ground. She bit him after that, and he was transported into a fleshy ballroom where Paula exists as an angel. Or as a Fury, with six downy wings.

"My lungs are heaving from many tiring struggles; I have visited every corner of the earth," the Fury goddesses of vengeance say when approaching Orestes, the mother-killer, in Aeschylus' Eumenides. "I have visited every corner of the earth, and I have come over the sea in wingless flight, pursuing him."

Paula, too, is exhausted from her chthonic destiny.

"If you truly loved me," she wonders out loud, "why didn't you die with me? Why did you make me suffer, all alone? [...] Why are the demons after me? Is it because of you? Why must I suffer because of you? What about me? Where is my freedom?"

I'd always heard people say that recovery is nonlinear, that there's no guarantee that feeling better today, or this month, will save you from future heartache. The idea is you become better equipped to deal with it.

I understand the sentiment in theory, but I'd hoped it didn't apply to me. I felt like I had conquered more than a decade's worth of debilitating mental illness, abuse, and pain. How could I ever get back to that place?

Quickly. All of a sudden, like someone changed the locks on my door when I wasn't looking. In the relapse, it's unreal. My anxiety has sometimes made me feel so empty that it's confusing to look down at my hands and find that they can still make contact with the world — my boyfriend's face, my lap, cold soda. Aspiring to be Judy Garland and Marilyn Monroe, I fantasize about blue pills and warm milk to make me fall asleep.

But I'm awake at 4AM, 5AM, 6AM, 7AM… Through my eyelashes and, other times, through tears, I observe as my bedroom shifts from the velveteen darkness of the middle of the night to the streaky blue of early morning. I will myself to stand up, and so I do.

Then I walk through the world with black boots on, a black skirt, and my black hair streaming down my back, and I'm insecure about how normal I must appear to other people. I'm speaking and smiling with blackened determination just like they are. But inside my skin, it feels as if I might fissure like old wood. I can hear my heart beating as if it's the wind pounding at the roof of an empty house. All of my bones ache from exhaustion, and I can hardly believe I'm breathing. If my body's given up on falling asleep and dreaming, why not on air, too, the untouchable fabric of dreams?

It's not fair. I've been good for so long. Why are the demons after me?

"When the passion for expiation / is chronic, fierce, you do not choose / the way you live," the poet Louise Glück writes in "Persephone the Wanderer." "You do not live; / you are not allowed to die."

What about me? Where is my freedom?

Garcia asks his incensed Paula to forgive him, which she impolitely declines.

"Whoever commits an offense, as this man has, and hides his blood-stained hands," sing Aeschylus' Furies, "we are reliable witnesses against him, and we are avengers of bloodshed, coming to the aid of the dead."

To finally enact retribution for herself, and for the countless deaths she's had to endure, shrieking Paula begins her attack against you, Garcia, who lumberingly tries to find an exit. You help him do this by feeding a palm-sized eyeball to a demon baby, who, pacified, unlocks a door in the seemingly intestinal boss chamber Paula has created.

Now, Johnson instructs you, it's time to convince Paula to leave with you. But as we've established, all you really know is how to fire your weapon. So you do, loading bullets into your rightfully wrathful girlfriend, whose wings turn black as she pulls an avalanche of blood up from the ground and sends small tornados hurtling at your head.

You win, in the end, because death is Paula's fate in Shadows of the Damned. As a myth, in the form of the legendary demon huntress, and as a woman, Paula is meant for tragedy.

"Myth is a system of communication," Roland Barthes writes in his 1957 essay collection Mythologies. Through centuries of sculpture, song, games, and glances, people have created the convincing myth that to be a woman is to be a shattered bone. In Ancient Greece and Shadows of the Damned, women are debased, criticized, and made crazy. They're attacked and romanced — always acted upon, rarely acting.

But Paula is gracious about her defeat. She's gentle. She sits on the ground, crying into her dress, though she allows Garcia to hold her and soak up some of her misery. Here, Garcia is dignified, too. Even as rapidly approaching Darkness seemingly turns his health bar into nothing, he keeps his arms tightly wrapped around her.

It doesn't seem like they'll ever fully be free from the demons that have latched onto their backs. But they don't mind.

"I have already found my escape," Garcia sighs, with sunlight in his voice.

I can't stop thinking about how Persephone was brought deep below the wet earth to sit on the demon king's bed and pick at her bowl of pomegranate seeds. It must be difficult to have an appetite when spirits are watching you, collecting at your feet like rainwater, waiting to see if you'll spread your legs.

Hagar the slave is raped by her 86-year-old master in the Book of Genesis. She runs for the terracotta desert and walks by the spring water. It's purer than the speckled sky that hangs like a crooked picture over the house she fled. Unlike that dreaded home, the desert is an open-plan hell. All Hagar can see for miles confirms what she already felt in her stomach: we must burn to exist. An angel comes to tell her she is pregnant.

The Egyptian goddess Isis is very resourceful and reassembles her dead brother's shattered limbs so that she can have sex with him again. Reborn, like gold melted down into the shape of a penis, Isis' brother Osiris becomes king of the underworld. Isis becomes a wife and a necromancer.

Spell for raising the dead

- 1 tbsp. lavender, dried

- ½ cup sandalwood, dried

- ½ cup of yarrow root

- Three strong yew branches

- Nine holly leaves

- Framed photo of the deceased

Under a waxing moon, place a pinch of lavender and sandalwood in a fire-proof dish to burn as incense. Put the photo down on the altar and arrange yew branches in the shape of a triangle around it. Add yarrow into the center. As you light the incense mixture, visualize the deceased while repeating these words: "I remember, I remember; I'll make it up to you."

Leave the altar untouched for three weeks. On the third Friday, after midnight, quietly retrieve holly leaves and wrap them in clean white cloth. Place the bundle under the pillow and picture the deceased as you lay there. In the morning, the deceased will be standing in your doorway. If you were, in fact, the deceased, it's okay. You're safe.

There's a myth in The Brothers Karamazov about a terrible peasant woman who demons happily drag into a lake of fire. She swims until her guardian angel tries to save her, though she shirks God's kindness and learns nothing. "So the angel wept and went away," Dostoevsky writes.

There must be miracles I miss when I'm not looking. Love is the sap of the Tree of Life; I should rinse my hands and welcome it.

Shadows of the Damned includes an epilogue in which Garcia and Paula eat burgers and organic Caprese salad. Suddenly, Garcia gets a phone call — it seems like it's Fleming, extolling the virtues of human burger patties.

He's visibly shaken, but Garcia doesn't want to fixate on it. He's planning on taking a weekend trip to Mexico with Paula, and he encourages her to book a hotel, ASAP. But then Paula screams, an all-too-familiar sound.

Her last words before Stygian black feathers burst out from her chest, staining her clothes with midnight, are: "Garcia! No!"

Garcia catches Paula before she can collapse on the ground. "Here we go again," he says like her neverending death spiral is a trip to a crowded grocery store. "Fate has led me to fall in love with the Lord of the Underworld's mistress."

How cruel. She has heterochromia — one of Paula's eyes appears as a glossy turquoise marble while the other is a snowcap cataract — a pool and an iceberg. I have physical anisocoria, my olive pit pupils are a few millimeters apart in size. Are these strange eyes the reason for our fates?

I don't know. I guess the important thing is to keep enduring it. Several times while playing Shadows of the Damned, I'm overwhelmed by how unfair Paula's situation is. And yet she never decides to take matters into her own hands, stabbing herself in the neck or sticking her head into a lake of fire and ending it all for good. She just keeps dying, because she has to. Paula dies to survive the moments in between each death, the few minutes she's allotted to breathe. She always whips her head around her with a wild fox's look, either terrified or angry. When demons come for her again at the end of Shadows, after all she's experienced, her iceberg eye turns the color of strawberry jam. I see my life and the many deaths that have come to blight it through similar, reddened eyes.

But we have to keep dying, me and Paula, Paula, and the rest of the world that is as steeped in black tea shadows as Shadows of the Damned's twilight city. We sacrifice ourselves in order to exist for the sake of life itself, which requires nothing, really, except for your heart to beat and lungs to work. There must be something that makes this dedication to survival worth it. Like love, or some other glimpse of heaven.

Subscribe